#4: Console better.

The profound power of bearing witness, sharing stories, and asking questions.

Consolation feels like an old-school, outdated word.

Like a word your grandma uses.

We don’t toss this word around in everyday vernacular. And when we do happen to hear it, we tend to think of a consolation prize (what you get for not winning), rather than the act — the action — of consoling.

Empathy, sympathy, compassion… these words easily flow through our lips when we describe connecting with and caring for each other. They’re good words, to be sure.

But these are feeling words, centering our own internal experience.

Consolation — what you actively do for another; when you actually reach out, through your empathy, sympathy, compassion, to touch the grieving soul — is nowhere to be found.

Maybe that’s why we are so unskilled at it.

I think we are often scared to console, fearing we might make the pain worse… My friends, there is very little you can do to make it worse.

The mind of a grieving person is ink black. When your intent is to console, you won’t accidentally add any darkness. But you can purposefully add light.

Step 1 of consoling: Breathing through “the freeze.”

When those we care about lose someone, we feel for them and hate to see them in pain.

(There is actually a biological thing going on here, but we’ll address that in a future post.)

We think to ourselves, “Oh please, can’t we do something? Can’t we make it better? Couldn’t we have stopped it in the first place?”

So why do so many of us freeze up and do nothing?

I would argue it's because — in our general squeamishness around death — we have gotten lost in our own fear, slipped into auto-pilot, and distanced ourselves from the whole “situation”…

Instead of staying focused on the people who really need solace.

(To be fair, it’s hard to stay present and purposeful in the face of grief without either a strategy or practice. Which is why we’re here!)

So the first step in consoling better is ensuring you are putting the loved one who has lost at the center of the experience.

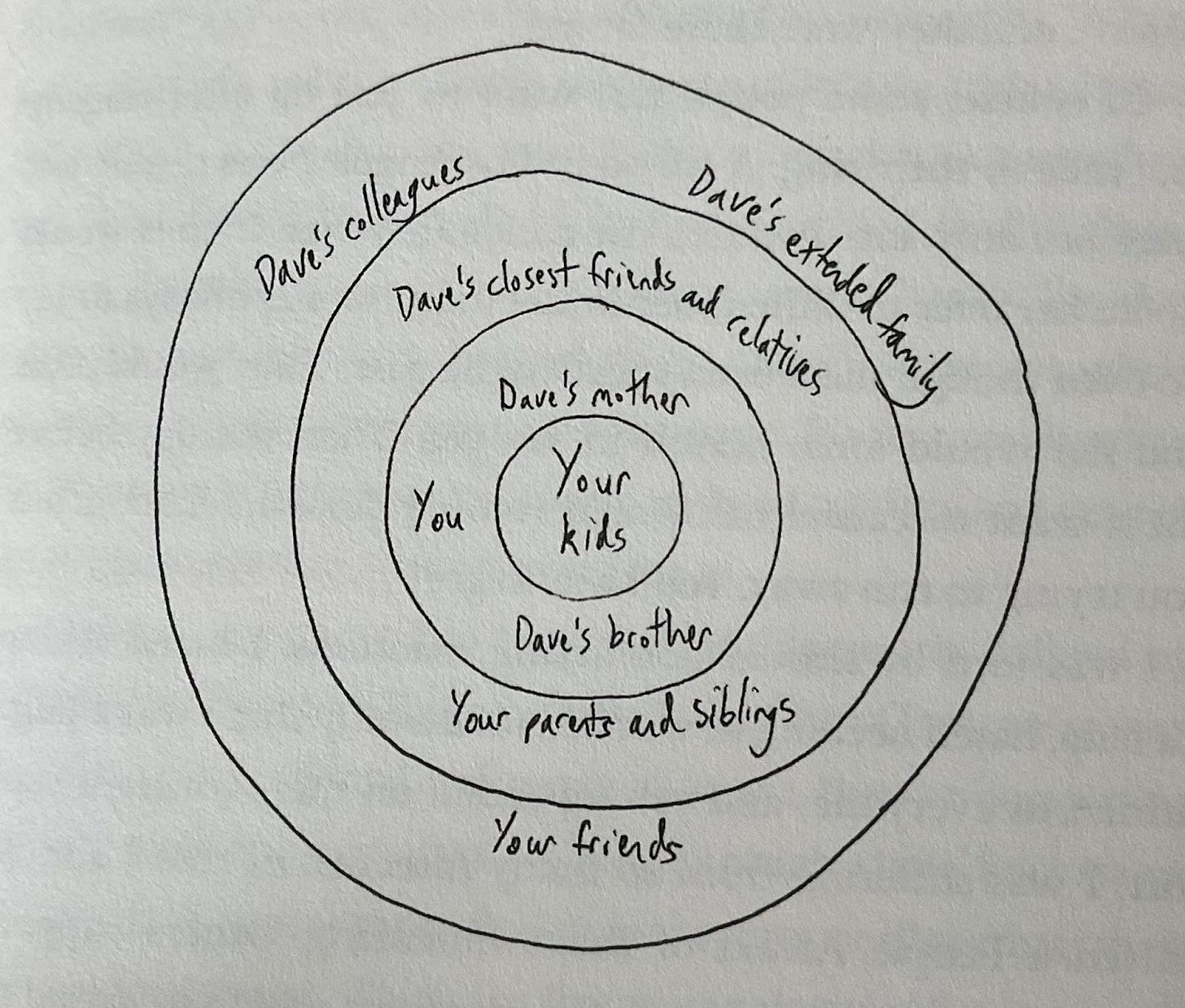

In the book Option B by Cheryl Sandberg and Adam Grant, Adam uses a visual to show Cheryl how this idea works after her husband Dave dies unexpectedly of a heart attack.

Those most impacted — and most in need of consolation — belong at the center. Each concentric circle holds other humans, radiating outward to reflect how much their life is impacted by the loved one’s death.

I really appreciate this idea because it clarifies who needs the lion’s share of our support. It gets us focused.

And this focus is the anti-venom for what tends to come next when we encounter grief…

Our mind’s slide down the slippery slope.

The thought of death bleeds through our consciousness and morphs into a personal experience — it shifts from being centered on the other person to something that is conjuring up our own fears.

Next thing we know, our minds begin to circle the wagons and care for the other person goes out the window as our worst fears take up all our mental space, convincing us we need to protect ourselves.

It’s normal. It’s natural. And here’s what you do about it.

When you feel the poisonous gas of fear seeping into your own mind:

acknowledge it;

find your way back to reality with deep breaths;

reconnect with what really matters: your love for the grieving person in front of you

Let’s walk through my personal process together. It’s smoother than you’d expect.

When I feel the fear of another’s grief rising, I know it in my body first.

My hand instinctively jerks up, palm flat against my chest to protect my heart. (Sound familiar?)

The adrenaline floods in next, generating a prickly sensation that spreads out from the space under my hand.

In response, I pause, bow my head, and take a deep breath.

In that moment, fear gives way to sadness — sadness for their loss, sadness for what they are going through.

I know that feeling.

I don’t have experience with every kind of loss, but my motivation to console does not require identical experience.

It merely requires a movement from fear and sadness into love.

And so I let my sadness, sympathy, compassion — combined with focus on who really matters — remind me of how much I love them.

How, more than anything, I want to be here for them in this moment.

And how, surprisingly but surely, my heart can expand to hold them, all of them, including their grief.

Trust your heart. Get out of your head. Breathe. Don’t let your emotions talk you out of action. Not now, not when it really counts.

Because how often do we truly get the chance to improve others’ lives?

Loving others through their grief is one of the toughest things we are called on to do as humans. Rise to the challenge. In the process, you will change the griever’s life… and your own.

Step 2: The bare minimum matters.

We have rituals in our culture around loss: attending the funeral, bringing food for the family, sending sympathy cards. These are just table stakes. Do them all.

Let’s take a look at the seemingly least impactful act of consolation: sending a note.

After Mike died, I received floods of messages, emails, letters, cards. Some were more thoughtful and heartfelt than others. Some more well-written, some with misspellings. But I hardly noticed. I tore into each one, eager for the solace…

Because they all represented people who loved me or had loved Mike; who cared enough to do something.

These “niceties” demonstrated that Mike, and the family he had just left behind, would not be forgotten.

And although I could not see it at the time, they also demonstrated one of my foundational beliefs — that human connection is the path to a more vibrant life.

I was on the receiving end of tangible artifacts channeling connection.

And with each one, I felt a little less alone.

But that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Why stop at supportive when we can reach life-changing?

Step 3: The little things that make the big difference.

Here are three choices. Pick one when you are doing the hard work of consolation, either in a written message, a voicemail, or face-to-face, tissues at the ready.

Option 1: Be a witness

Option 2: Tell a story

Option 3: Ask a question

Be a witness.

In his song “Place to Start,” Mike Shinoda laments the feeling of being left behind after his Linkin Park bandmate Chester Bennington died by suicide.

The song aptly describes our confusion after abrupt loss with the lyrics, I don’t need to know the end, all I want is a place to start.

What most moves me about the song comes at the very end where Shinoda includes a series of voicemails from his friends. They are checking in, expressing their love and support, and not expecting a call back.

They are bearing witness to his suffering.

Innate in witnessing is the consolation of comfort. Checking in through a text or a voicemail is comfort. Your presence alongside someone is comfort. Your listening ear, firm hug, shared tears — all of these are comfort.

Comfort is the life preserver we must toss to anyone sinking into the deep loneliness that accompanies grief.

It may not be able to pull one back in the boat but it helps them survive for the moment. It ensures the griever continues to float… until they are strong enough to pull themselves aboard.

Bearing witness is about abiding alongside those who have lost — just being with them as they struggle through the waves in their journey.

Not fixing, not solving, not offering advice.

Just being.

When we are grieving, it is all we can do to survive — to float.

And someone sitting there with us — without explaining to us that we just need to learn how to swim, that we never should have been in the ocean in the first place, that they once had a friend floating in the ocean, or that all floating happens for a reason — dignifies us.

It honors that we are doing the best we can.

Often people trying to fix, solve, give advice inadvertently cause their grieving loved one to feel worse. Like they could be doing better… should be doing better.

But I believe grieving is the best thing they can be doing.

I believe grief is a deep alchemical process with transformative powers our rational minds can't understand.

So simply supporting someone’s grieving process with your presence, your comfort, your witness is far more powerful than any advice anyone could offer.

Tell a story.

In the weeks after my husband’s death, I would walk down to the mailbox every afternoon, making the return trip back up the driveway with an armful of randomly sized envelopes, packages, fliers, and catalogs.

I’d separate out the bills, insurance forms, and all the other white-business-envelope-sized torturous paperwork of death. Then I would take all the colored Hallmark-envelope-sized missives or odd shaped packets, set them in a pile, and settle in for some reading.

Reading about Mike.

People sent me pictures, poems and prayer cards, tiny angel and cardinal pins, ribbons, children’s crayon pictures… ephemera which were all direct expressions of consolation. I held these all dear.

If I opened a card or envelope and saw cursive handwriting filling the paper, I knew that meant a story. Stories were my favorite…

Stories of how Mike mentored them and made them better at work.

Stories of how Mike was a kind and caring friend during their college years.

Stories of how Mike’s singing voice was the thing they remembered best about him all these years later.

Stories about how his team would try to get him to put mayonnaise on his sandwich at lunch but he was too much of a health nut to do it.

Stories about angry clients that Mike calmly responded to by pulling all-nighters, studying all the issues and eventually, invariably coming up with a solution that calmed the client down and saved the day.

And stories about how much his love for his family showed through in everything he did.

I loved them so much I saved them all. Seriously, I’ve got boxes. Because these stories told me something new about my husband.

Yes of course, I knew he was a great mentor, kind, quirky, and an amazing singer who loved his family. But these people were sharing an interaction they had with Mike that I had not experienced. With each retelling he came alive for me again.

These stories became my treasure.

Because anyone who has lost someone is now clutching their memories for dear life, fearful of losing a single one, because they know they won’t be adding more…

And when you share with them a story only you know, you give them an infusion — transforming their lost loved one from a two-dimensional photo back into the dynamic being they were.

You give them something to add to their experience in the midst of so much being taken away.

It will be their treasure too.

Ask a question.

I have a very large collection of books on life after loss. In the early months of my grief, I could not stomach the “how to” books — the proscriptive way of dealing with my blown-up world. (Remember when I was talking about how “advice” can sometimes be counterproductive to the grieving process?)

What I could read were memoirs — descriptive stories of how people dealt with their own loss or their imminent deaths. I referred to these books as the “Grief Canon”.

In an incandescent little book titled A Month in Siena, Pulitzer-Prize-winning author Hisham Matar takes his own month of consolation after writing a heart-rending memoir on the ambiguous loss of his father in the Libyan Civil War.

Touched by death, his openness to others’ grief can be a model for us all.

Hisham is having a light conversation with his Italian language tutor over an ice cream when the conversation turns to her father. She shares that he died just one year before.

“Tell me about him,” Hisham says.

This allows her to share a story about her late father’s love of Dante, and brings her father’s presence there between them for a few moments. Yes, there is sadness. But there is laughter too. And most importantly, love.

(Note that many people would apologetically change the topic in order to “save” the person in front of us from having to reopen a tender wound. I think we partially do this because we are saving ourselves.)

Similarly to retelling memories, when we ask a question to the living about their lost, we breathe new life back into their loved one.

We allow them to commune with that lost relationship, to reignite that lost love, to remember fondly rather than solely with pain.

Then a piece of that love can live on in us — the outsider — as well. What a gift.

In summary

This is my attempt at bringing consolation back into our lexicon.

And much more importantly, into our actions.

So…

Be a witness.

Tell a story.

Ask a question.

If you are already confident in your powers of consolation, fantastic. Share some of your ideas with me in the comments below!

Then go forth and act.

Don’t overthink it. Do it. Console better.

In consolation,

Sue

Really appreciate the explanation of why advice can actually be counterproductive. It also explains why - in other hard moments beyond just grief - a friend giving me advice can make me more upset... that’s a big lightbulb moment! Thanks again Sue 💜

This is so insightful. And I just saw it in action, not in response to a death but in response to the loss of a hope, a dream, an expectation. My daughters friends reached out to her to console her. They knew before she could even tell them how devastated she was. One of them even left her a voicemail in tears telling her how she loved her and how phenomenal she is. We know how to do this. Sue is so right. It’s just covered up in layers of our own fear.