#128: Screw self-reliance.

What the forest teaches us about the real source of human resilience.

The Luminist is a reader-supported publication that illuminates the pain, the pleasure, and the paradox on the path to technicolor living. Subscribe below to receive posts about how loss teaches us to get the most out of life (along with silly gifs) in your inbox every Saturday.

As the miles unfolded on my six-hour drive to Colgate this past weekend, I watched spring transform through my windshield.

At my Virginia jumping-off point, a sheer tablecloth of bright green draped the dark trunks, new leaves neon in the sun. As I got farther north, the tablecloth fell to the ground, the only green in sight carpeting the fields and meadows, tree buds still tight in their winter slumber.

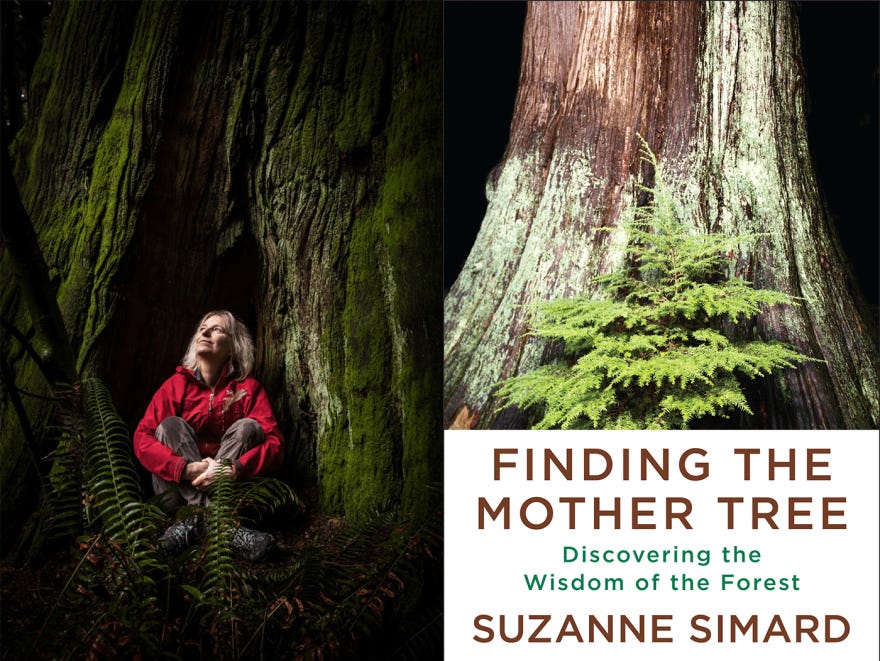

While my eyes took in the changing landscape, my ears were learning the forest's secrets through an audiobook of Suzanne Simard's Finding the Mother Tree. Her lilting Canadian voice described something extraordinary happening beneath the surface soil of those woods I was driving past. Trees aren't standalone giants competing for resources — they're connected by fungal networks that share nutrients like carbon and water. The journal Nature dubbed her discovery the "Wood Wide Web."

I sighed with recognition and relief. I’ve been trying for YEARS to describe the invisible net of support that caught me and the kids after Mike died. To explain why it’s not just “nice to have”, but essential on this life rollercoaster. To capture it’s organic, subtle nature.

Simard and the forest finally gave me the language I’ve been looking for.

We throw around "it takes a village" like it's gospel, but let's be honest — we don’t act like it.

We attribute our successes to ourselves alone. (Rugged individualism all the way, baby.)

We withdraw when times get hard. (Nothing to see here.)

We pretend we don't need help until we're drowning in our own stubborn independence.

Meanwhile, trees have been quietly thriving through connection for approximately forever. There's no tree TED Talk about "Ten Steps to Forest Domination." There's just an inherent recognition that when you thrive, I thrive. When you struggle, we all feel it.

Which is actually JUST like humans. We all have our own ecosystems, invisible but vital, sometimes ignored but always there. The coworker who gives you a ride to pick your car up from the mechanic. The old friend who always answers your call. The aunt who still sends you a crisp $20 bill for your birthday.

I could point to the anthropological, physiological, and archeological evidence that we are social creatures. But let’s just look at something more concrete: the feeling of confidence. The willingness to put yourself out there, to take a risk, make a bet, and give it everything you’ve got. Without people who have our back, we don’t take the risks. Without others believing in us, we don’t believe in ourselves. Sure, in theory we could do these things alone, but we don’t. Because without others we are in survival mode, not change-the-world mode.

Every single mom can tell you that those “self-made success stories” are complete bullshit. We just don’t like to admit it.

When I finally arrived on campus after the long drive, Connor was mad-dashing between preparations for a frisbee tournament and the final a cappella concert of his college career. He carved out time for a quick diner dinner. Over my club sandwich and his quesadilla, I watched his human forest unfold.

"The frisbee team's staying at the Econo Lodge next weekend," he said, typing a quick text. "I've got the car assignments sorted. I should probably check with C.J. to make sure he paid the registration fee."

He took a bite, shifting gears. "Professor Brown finally admitted that she thinks my French accent is improving — after four years! She made me promise to keep in touch after I graduate. It feels good to have, like, a mentor.”

Between bites: "Oh, and that freshman Econ student came for tutoring yesterday, totally panicking about the next exam. Two hours later? Complete turnaround. You could literally see the equations clicking into place in her head."

Here I was, thinking I was just watching my kid eat a quesadilla, when I was actually seeing a living, breathing ecosystem in action. His a cappella group supporting his creative expression. The frisbee team forming a sweaty but surprisingly organized family. His professor offering mentorship. His tutoring job letting him pay forward what he's learned.

Kendall's networks look completely different but are just as rich. High school friends scattered across the country but thick as thieves through their infamous group chat. The barn where she connects with her aging pony Frank, still able to sink into their old rhythm and jump some rails. Her college friends learning how to “adult” together, sometimes stumbling, always catching each other.

They're both building forests that will sustain them through whatever storms come their way. It doesn’t matter if they’re doing it consciously or not, it’s just what humans do.

There’s a myth about connections that I believe keeps us from leaning into them.

We think that the give-and-take between friends, colleagues, partners should always be equal. But resilient bonds aren’t static — they fluctuate and evolve. Sometimes we're in receive mode, drawing strength when life knocks us flat. Sometimes we're in transmit mode, feeding energy back into our communities. And occasionally, we experience what I can only think to call kumbaya mode, those rare moments when the system hums in perfect balance.

I used to be terrible at receive mode. Like, Olympic-level terrible. When someone offered help, I'd smile brightly while backing toward the nearest exit. "No, no, I'm fine! Totally fine! Never been better! Do you smell smoke? I should check on that!"

Then life handed me a situation where "I've got this" simply wasn't an option. And I discovered something surprising: letting people help me didn't diminish me. It strengthened our entire ecosystem.

This rhythm of giving and receiving isn't something most of us were ever taught. We operate as if there's some cosmic scoreboard tracking who's given what to whom.

But networks don't keep score. They just keep taking care of each other, and keep growing because of it.

There's one more remarkable thing that Dr. Simard discovered.

When a mother tree — a tree that has become a central hub of the forest network — comes to the end of its life, it doesn't just die. It gives a final burst of nutrients to its web. A surge that helps its saplings survive and their supporting ecosystem thrive.

Mike was our mother tree.

The day after the funeral, I found myself surrounded by a forest I hadn't fully recognized before. Parents I barely knew arranged playdates for the kids. Family quietly repaired the house and got the oil changed in my car. Friends patiently helped me through mountains of gibberish paperwork. Neighbors shoveled my drive without ever being asked.

I'd always thought of ourselves as independent. Strong. Capable. We were, of course, but not in the way I'd imagined. We were strong because we were connected. We were capable because we were supported.

The physics of grief should have flattened us.

That's what most people would predict: father gone, mother broken, children lost.

Instead, our forest grew denser. Not because loss itself strengthens, but because Mike had been steadily building connections his entire life. And as his final gift, he gave us everything he had.

Our entire cultural mythology centers around standing alone, facing challenges with nothing but grit and a montage sequence. We celebrate the summit photo but ignore the Sherpas, the support crew, the partner who facilitated our training for months, the friends cheering us on.

What if we celebrated our connections instead? What if we acknowledged our interdependence as strength rather than weakness?

Because the storms will come. They always do. The only question is whether we’ll face them alone, or surrounded by a forest that's been preparing for this moment all along.

In connection,

As I sit here reading, someone I care about, who cares about me, is outside doing some difficult physical work. It's all I can do to let him do it. I want to run out and bellow a string of reasons that he shouldn't help me. I let my web help me after my husband died, but the web moved to other trees and I found myself alone. And I'm having to learn to let my new web help now. Thank you.

As someone working on releasing my attachment to being “the helper,” I really appreciate this post. The bit about transmit vs receive more is especially resonant.