#49: How to console when you’d rather run away.

A new way of relating with our discomfort around death and grief.

The Luminist is a reader-supported publication that illuminates the pain, the pleasure, and the paradox on the path to technicolor living. If you like The Luminist and want to help spread its message, tap the ♥️ and/or 🔁 button to help more people find it.

Prior to starting The Luminist, I spent a ton of time trying to figure out what the hell I was actually going to say in it.

During this planning phase, I channeled my corporate wonk skills and developed a snappy elevator pitch to convey my intent: Shining a light on grief, death, and loss in order to console better, suffer less, and lead more vibrant lives.

But it’s been almost a year since posting my intent online and writing about it every week. So I’m looking backward, assessing how this tagline jibes with what we’ve actually tackled.

Grief, death and loss? Check! These themes are woven through our posts. But maybe not in the way I originally envisioned. They are the dock from which every boat — or post — is launched. My intimate relationship with grief adds a unique spin to the ideas we explore here, even when the topics — making time for rest; balancing the journey with the destination; embracing failing; managing risk — have (seemingly) nothing to do with them. ‘Suffer less’ and ‘lead more vibrant lives’ are also constant TL takeaways, since we are unapologetically self-help.

Consolation, however, has slipped through the cracks since post #4! I’m a little disappointed in myself… But maybe I’m not talking about consolation here so much because it’s already a big part of my daily life.

As a 55-year-old with a cluster of friends a decade plus-or-minus, I’m smack dab in the ‘aging parents’ demographic. I’m also unfortunately in the ‘unpredictable bad things that befall people and end their lives’ demographic too. As a veteran of loss, I am often first to the grief scene, offering a hand to hold and a shoulder to cry on. I consider it one of my sacred duties since I was initiated into widowhood.

But now, three weeks away from TL’s one-year anniversary, consolation feels important to weave back into this corner of the internet.

Because consolation can make a big difference in someone’s life… And we have so much to learn about giving support during one of the most common experiences in life.

I like ‘consolation’ because it is an action-oriented word.

We can have sympathy for someone inside our own hearts and heads. But we can’t say we’ve consoled until we’ve taken action in the external world.

However, taking the tangible step from feeling sympathy to giving consolation can be hard, because… well, we’re afraid.

When death is in the picture, fear can’t help but occupy a big part of our mental real estate. Our actions then get hijacked by our emotions, which can override even our best intentions. We end up feeling like we need to protect ourselves… which usually means avoiding rather than consoling.

I didn’t always believe people had good intentions — that people wanted to console. In fact, I would tell my BFF Julie stories about acquaintances who would avoid me or not talk to me about Mike’s death.

“Anyone who can’t engage with me on this is a coward!” I would rail. “Why are they prioritizing their own comfort over my suffering?”

Ever wise and accustomed to my scorched-earth tactics, she would bring me back to the green surface of the planet.

“People are just afraid. Afraid of dying. Afraid of saying the wrong thing. Or just maybe afraid of what you make them feel,” Julie counseled.

Fear makes us tell stories to our brain that are patently false. Our fear runs a movie on the inside of our skull featuring two characters — us (aka the consoler) and the griever. Three frames in, we’ve made the griever cry. On the fourth, we’re crying too. Roll the end credits and blooper reel! High tail it out of the movie theater!

When our emotions lead the way, justifications for non-action bubble up in the place where consolation should be. We don’t help anyone and we end up making our world smaller — ever narrowed by the things we avoid in order to not feel what it’s perfectly human to feel.

There are many strategies for pushing through fear to do something anyway.

But as the newly minted president of the Feel Your Feelings Society, I cannot condone such action. (Except obviously in emergencies — I’m emotional, not foolish.) Besides, it doesn’t make us very good consolers. Consoling is all about offering comfort amidst emotion, not trying to wipe emotion off the face of the map. Practicing on our own feelings seems like a good place to start.

So if we commit to not simply running away from the source of our fear… what then is our fear asking of us?

According to

, beloved TL editor and author of , “Our bodies, our emotions, our stress responses don’t need solutions. They need to be heard. Once the message has been received — the mind has honored what the body is feeling; the body trusts it is being taken care of — the mind can do what it does best. Handle shit.”I want to say that again. Our emotions just need to be heard. They need to know their message was received. They don’t need to be shut down, ignored, or berated.

Leona coaches us in her post that, when fight or flight is not an appropriate response, we can simply let fear wash through us without reacting to it. Because we aren’t in physical danger, we don’t have to do anything with the feeling. Just acknowledging that the emotion has been seen and heard is enough. And remembering that everything is going to be alright.

When I close my eyes and imagine going through this process, I feel comforted. Nothing has actually changed but I feel more at peace.

And this is exactly what the grievers of the world need from us too. We can’t change their pain but we can acknowledge it exists. And show them we’re not going to shut it down, ignore it, berate it, or run away from it.

Our smart brains are sometimes dumb in the face of others’ grief.

We overthink things or try to apply inappropriate strategies or just assume that grievers are aliens because we can’t empathize with their situation and therefore don’t know how to act around them.

In case you haven’t been initiated by the fires of grief, here are some other rules-of-thumb for consoling effectively:

Channel Mr. Fix-It appropriately.

We like to fix things. That’s what we were trained to do in school and are paid to do at work. It’s our gear. But there is no fixing death and there is no fixing grief.

So once you are out of your head (having felt your feels), take some time to just sit with and listen to the griever. Grief is incredibly isolating, so while you may feel like you’re not doing anything, just being present is a huge comfort.

And then, if you’re feeling like you absolutely have to do something tangible otherwise you’re going to jump out of your skin, start to pay attention to the needs the griever is expressing. Because while you can’t fix their inner state (and please don’t try, don’t point out a silver lining or say “buck up!”, it’s too soon, it’s always too soon), I’m sure there’s something helpful you can do in the external world, like:

Starting a dinner donation chain

Taking her car to the shop

Picking up a kid from practice

Helping with Christmas shopping

People did all of these for me, and it was a tremendous help. Tactically and emotionally.

Just remember, you’re not fixing the emotion. Rather, you’re listening compassionately, and then, after you’ve hugged the griever goodbye, you’re getting to work to “fix” a need they have.

Maintain their meaning.

Loss takes a piece of our identity away. So grievers often cling to the part of ourselves that still exists — whether it’s work, book club, a sports team, or our drum circle.

But when we return to work, for example, and people treat us differently, the solace we thought we’d receive just by existing as our work selves evaporates. Another leg of our identity stool, kicked out from underneath us.

When I began a new job five months after Mike died, I had a peer who just didn’t know what to do with the fact that I was a widow. At one point he told the head of HR, “Well, I don’t want to go toe-to-toe with her in a meeting when I disagree with her. I mean, she’s a widow.”

Reader, I am one tough nut, but upon hearing that story from HR I slunk down the hall to my office, shut the door, and had a good cry. All I wanted was to be myself and contribute, not to be defined by my loss. This guy was pulling punches because of a weakness he perceived in me. But work was the one place I felt strong.

Doesn’t matter the activity, it just matters that the griever has one place in their life that doesn’t feel utterly demolished by their loss.

I’m not saying, “act like nothing happened.” That would be callous at worst and inauthentic at best. But a simple, “I’m with you,” goes a long way. Then get back to drumming, book-discussing, foul-shot-practicing, or texting snarky comments via your under-the-table iPhone in tedious meetings. That’s the kind of normalcy grievers need.

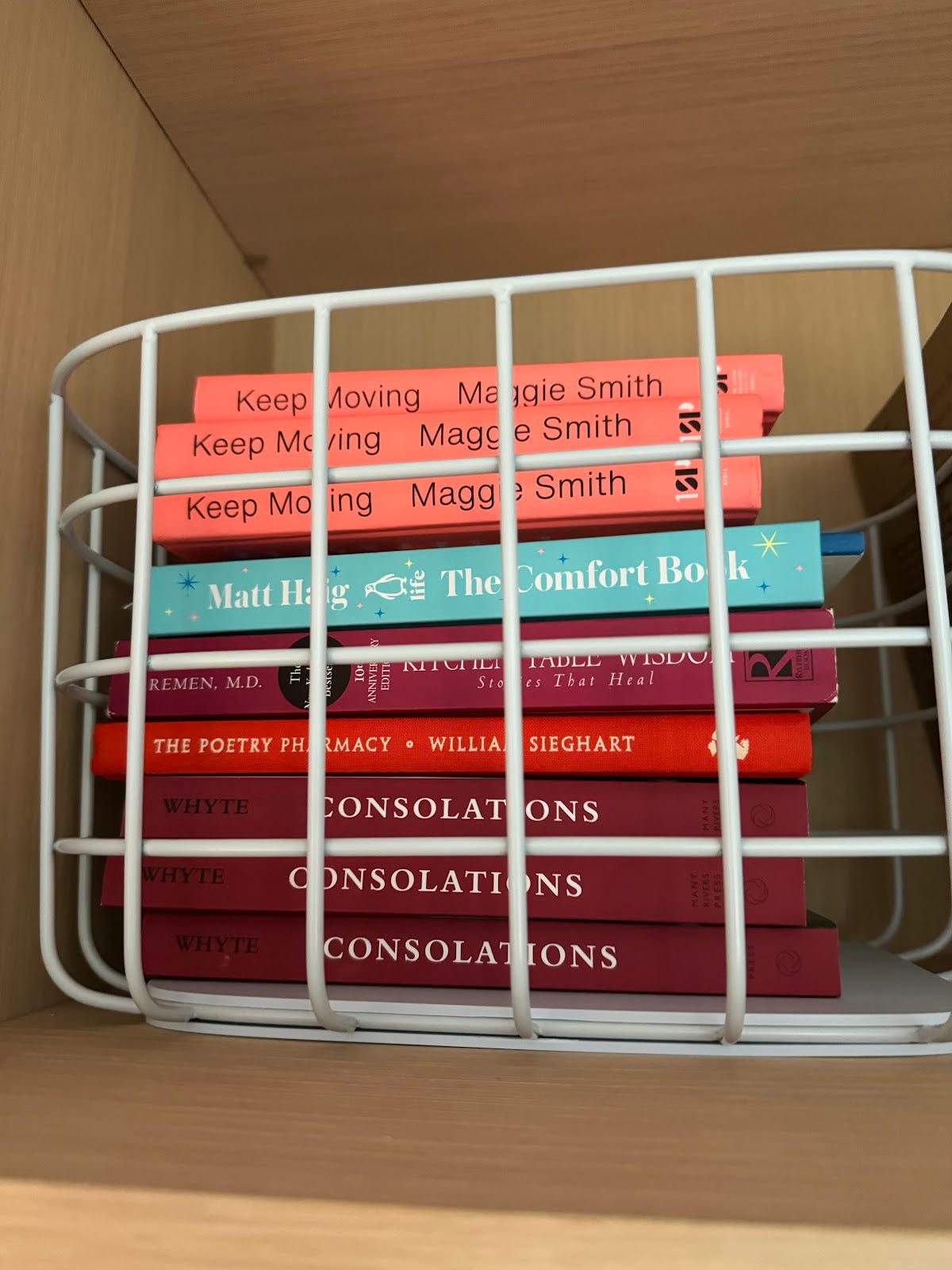

Employ a classic consolation strategy.

Option 1: Tell a Story

Option 2: Ask a Question

Option 3: Be a Witness

It’s not one-size-fits-all. It’s about what you have to offer the griever. In this case, it’s all about you.

Did you know the person they lost? Tell a story. Like the myriad consolation letters I received from Mike’s colleagues with funny work stories or profound instances of his mentoring, each story brought me a new way of understanding my husband, even though he was gone.

Do you have a chance to be with the griever one-on-one? Ask a question. There are few more consoling questions than, “What was she like?” or “Tell me your favorite thing about him.” I’ll talk your ear off about Mike every time I am given the chance. And when I tell you about him, you’ll understand just a little more about me.

Do you want to support but don’t know how? Be a witness. Attend the funeral. Send a card. Shoot them a text letting them know they can always reach out, but they don’t have to respond. Gently remind them that they are not alone.

(My original consolation post goes into greater detail on these strategies.)

When I began my new job six years ago, I met my great friend Mike.

(Since my Mike died, new Mikes show up in my life whenever I need them!)

Our work duties intersect so we’ve spent countless hours together. He’s been with me when other people ask, “What does your husband do?” And when I tell them, they flee… but Mike stays. He’s been with me during hard and teary-eyed moments when grief momentarily overcomes me. He offers me tissues. He’s listened to a thousand stories about Mike. He asks questions.

Mike shows us how simple it can be to console:

Over the days and months and years, just be there. Don’t let your fear trick you into running away. It’s grief, not a grizzly bear.

Learn to sit with your own fear, to let it speak its worries to you, and then rest its head on your shoulder. Before you know it, you’ll be able to do the same for others.

You don't have to show up with grand gestures, you just have to show up reliably. That is solace enough.

To all the consolers who saved my life,

Free & paid subscribers receive the exact same weekly content in their inboxes every Saturday morning. (The newsletter, vulnerable, personal, embarrassing stories, book recommendations, and whatever gifs have made me giggle.)

Considering upgrading to help myself and my editor Leona dedicate more time to The Luminist and support our current non-profit of choice: Experience Camps for grieving kids.

If you resonated with this post and want more, check out these:

#4: Console better. The profound power of bearing witness, sharing stories, and asking questions.

#5: Demystifying the griever’s mind. How stepping into the grieving mind allows us to be with others in the midst of their human experience… and our own.

#13: We are not islands. Releasing the myths of isolation and avoidance.

#14: Things will be great again. Giving each other permission to believe in the future while honoring the pain of the present.

#19: Where words can’t take us. Ritual and the human need to relate.

I somehow had missed this one! This is such wonderful, practical advice.

"Ask a question"—it's so simple, so effective at helping make a meaningful connection...and yet *so* easily forgotten! Thank you for the much-needed reminder.